A GNA feature by Samira Larbie

Accra, Aug. 25, GNA – On June 15, 2022, Alhassan Fuseini (Not real name), a 50-year-old man, forced a 15-year-old girl into marriage because his 10-year marriage to his 26-year-old first wife had not been blessed with any child and he wanted to have children.

However, even though his first wife consented to him taking on a second wife, she did not expect that he would bring home a child as a co-wife! The couple’s dilemma had been made worse.

Seven years ago, Imam Ismail Mumuni (Not his real name) also married off his 14-year-old daughter Hajara (not her real name) as a second wife to his friend Yusuf at Elubo in the Western Region of Ghana. She was only in Primary Five when her father married her off.

In the same neighbourhood, 14-year-old Ayisha Ibrahim was married off by her father who was afraid that she would be pushed into pre-marital sex to avoid the poverty the family has endured since she was born.

The three girls are representative of the over two million girls whose education is abruptly ended when they are married off due to religious, cultural, and misplaced fears that communities in Ghana still have.

Child marriage is any union either formal or informal, where one of the parties is under 18 years old is prohibited by law. Indeed, such marriages are considered a violation of human rights.

According to a UNICEF report, 15 million girls worldwide marry before their 18th birthday. A breakdown of the above reveals that 41,000 girls get married every day; 28 girls get married every minute and a girl gets married every two seconds.

The data also indicates that more than 700 million women alive today were married before their 18th birthday.

This is equivalent to 10 per cent of the world’s population (approximately 7.25 billion currently) six with around one in three (about 250 million) entering into the union before the age of 15.

The 2014 statistics also show that 156 million men alive today were married before the age of 18 whilst 33 million were married before the age of 15.

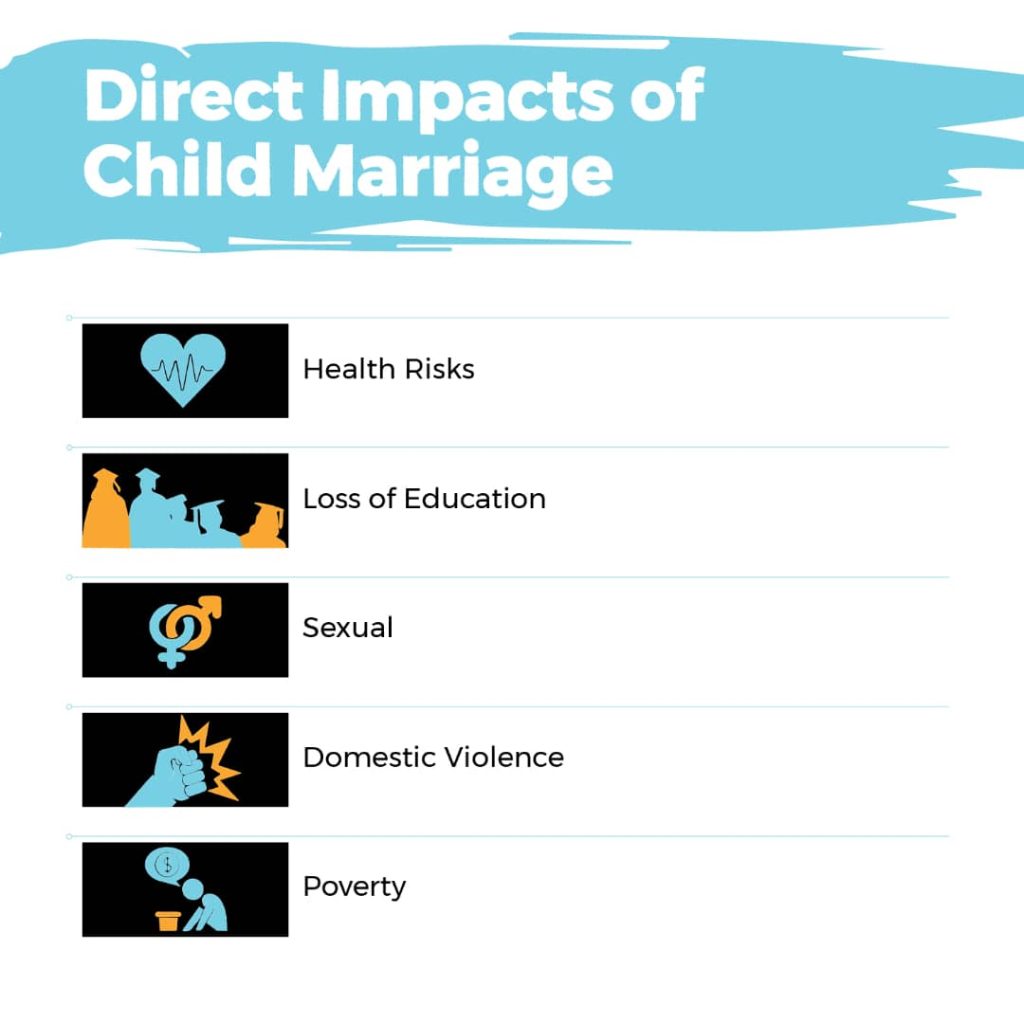

Children such as Hajara and Ayisha were denied their right to education, an opportunity to enjoy their childhood, and the right to choose when and whom to marry.

The public health implications for child marriages are enormous, contributing to the high maternal mortality rate, increasing the risk of sexual and gender-based violence, and increasing poverty and other socioeconomic challenges.

In Ghana, one in five girls aged between 20 and 24 years, married before the age of 18. A breakdown of the regional data from the 2014 Demographic Health Survey showed that the Northern Region recorded 39.6 per cent cases of child marriage, Upper West 37.3 per cent, Upper East 36.1 per cent, Western 32.9 per cent, Central 29.5 per cent, Eastern 27.5 per cent, Ashanti 25.9 per cent, Volta 25.9 per cent, Brong Ahafo 23.9 per cent and Greater Accra Region 18.5 per cent.

Factors

Some of the factors driving child marriage in Ghana include gender inequalities, teenage pregnancy, economic insecurity, ignorance, impunity, poor law enforcement and customary practices and social norms.

In some regions, the conflation of cultural and traditional practices with Islam has led to cases where imams condone child marriage, even though it is contrary to Islamic teachings.

Sheikh Armiyawo Shaib, the spokesperson for the National Chief Imam of Ghana, in an interview with the GNA said, in Islam, child marriages are prohibited.

“Even though the Quran does not fix the age of marriage, it does not support the marriage of a girl who has not attained maturity,” said Sheikh Armiyawo.

According to the hadith, the collected traditions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) based on his sayings and actions, the Prophet got married to Ayisha (r.t.a) when she was only six years old, but he consummated the marriage when she had reached the age of maturity. Maturity according to the hadith is the age of majority which is equated with attaining puberty and demonstrating adequate mental development.

Sheikh Armiyawo explained that when Ayisha (r.t.a) was betrothed to the Prophet (PBUH), she was handed over to Khadijah the Prophet’s first wife for training. The marriage was consummated when she reached the age of 18-19 years. According to Sheikh Armiyawo, a girl betrothed at an early age is not expected to live with her husband until she is fit for marital sexual relations (hata tutilqal-rijal).

“Betrothal can happen at any age, actual marriage comes later after attainment of puberty and sound judgment,” he said.

For a marriage to be established in Islam, there has to be a proposal by the groom and acceptance by the bride (al-Ijaab waalqubuul); and it is finally sealed with the payment of dowry by groom to the bride, he explained.

The dowry (mahr) is something that is paid by the man to his wife. It is paid to the wife and to her only as an honor and respect given to her to show that he (man) has a serious desire to marry her and not simply entering into a marriage contract.

This dowry is given with parents and family members from both sides as witnesses. It is only when she accepts the dowry that a marriage is established. Without dowry, no marriage is established,” he says.

Allah in Qur’an chapter (4:4) says “And give the women their dowries with a good heart”. This Quranic quotation makes early, child and forced marriages unaccepted in Islam, because in most cases parents often take the money without the knowledge of the girl, due to poverty.

The girl only gets to know after everything has been concluded, when she is told a man has come for her hand in marriage and she is prepared to be taken to her husband.

In such cases, the parents believe that the girls will be taken care of by the well-to-do men.

As in the case of Ayisha Ibrahim, who was married off at the age of 15, child marriage only entrenched the cycle of poverty. She told the GNA that her husband did not take care of her.

“I had to rely on my father to send me money to take care of my children and myself,” she said, adding that, she had to leave with her children after 25 years of frustration.

In some instances, the marriage is tied in the absence of these girls but in the presence of two witnesses (father and mother or uncles and aunties) from both sides and an Imam.

Sheikh Armiyawo said Muslim scholars and leaders need to correct the misconceptions surrounding religion and early marriage.

“There has to be a consensus to clear all the misconceptions. This kind of awareness should also target imams and Islamic teachers,” he said.

It is important to note that the drivers of child marriage in Muslim communities are by no means different from happenings in Christian communities.

Child marriage rates are high in some regions, despite being prohibited by the Children’s Act (Article 560), which states that no person shall force a child: to be betrothed, be the subject of a dowry transaction, or be married, and the minimum age of marriage shall be 18 years.

Sheikh Armiyawo said that in addition to changing attitudes, reducing poverty, and providing communities with socio-economic opportunities would help eliminate child marriage.

Nationally, the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection established a Child Marriage Unit in 2014 to promote and coordinate initiatives aimed at ending child marriage. Various non-governmental organisations also implement initiatives to fight child marriage. They include the Zakat and Sadaqa Trust Fund, which provides scholarships and other support to families who may be inclined to marry off their daughters due to poverty. The initiative backed by the Muslim Caucus and Staff of Parliament led by the National Chief Imam, Sheikh Doctor Osmanu Nuhu Sharubutu, provides families with food, shelter, education, health, and economic empowerment training.

“Providing skills training to girls who are at risk of child marriage, keeping the girls and boys in school through scholarships and the provision of free senior high school education, are just a few interventions that can encourage communities to break the cycle of early marriage,” said Sheikh Armiyawo.

In 2021, another non-governmental association, the Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG), introduced the Child Marriage-Free Community Alert Campaign, targeting 30 communities in six districts (Cape Coast Municipality, North Tongu District, Bongo District, Wa Municipality, Sagnarigu District and Asokore Mampong Municipality).

How it works

Chiefs sign a pledge to indicate that the community is committed to supporting the well-being of adolescent girls and preventing child marriage. After the agreement is signed, a flag is hoisted in front of the chief’s palace as a symbol of the community’s commitment to ending child marriage.

“If there is an incident of child marriage, the flag flies at half-mast until the child is rescued by the chiefs and police and reunited with the family. It is only when the child goes back to the parents and the marriage is annulled that the flag is hoisted again,” said PPAG Executive Director Ms Abena Adubea Amoah.

Children are also taught strategies to protect them from early marriage and to report child marriage to institutions such as the chiefs, the Police, the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit (DOVVSU), the National Commission For Civic Education (NCCE) and the Ghana Education Service.

Madam Khadija Yakubu (not her real name) told the GNA, that as a result of the campaign, when her 12-year-old daughter became pregnant, she did not marry her off to the man responsible as planned.

“I would rather have her deliver and return to school to be responsible in future,” she said.

Since the campaign was launched in 2021, six adolescent girls have been rescued from child marriage by the chief in collaboration with the police and DOVVSU in the community.

Despite these efforts by various national and international organisations, the signing of international resolutions and the enactment of national laws, child marriage in Ghana remains a concern. There is limited evidence that programme interventions to deal with the practice have made a dent on the practice.

This article was produced with the support of the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) with support from the Ford Foundation.

GNA