A news feature by James Amoh Junior

Accra, March 07, GNA – Dr Folashade Soulè, Senior Research Associate, Global Economic Governance Programme, University of Oxford, has observed that the diversification of security partnership, including non-traditional and non-state actors in the Sahel Region continues to breed security threats with spillovers in coastal West Africa.

She said the risks for coastal West Africa, including Ghana, Togo, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire were dire as the Sahel Region had become one of the most important centres of terrorism in the world with Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger being among the most affected.

According to her, several parts of Sahelian territories were no longer effectively controlled by the States leading to the rise of internally displaced population and the destabilisation of political regimes because of growing insecurity manifested by the high number of Coup d’états.

Dr Soulè, speaking at a public lecture on the topic: “The emerging role of new ‘security partners’ in the Sahel: what risks for coastal West Africa” at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD), University of Ghana, said both democratically elected and military regimes were being ousted calling to question the national security policies of those regions, but also foreign security partnerships, many of which were being challenged with increased defiance by Sahelian populations.

Specifically, speaking on the French Military presence in the Sahel, Dr Soulè said such partnerships were subject to increasingly harsh criticism from the population both by governments and civilians evidenced by the frequent number of demonstrations against their presence.

Dr Soulè said: “The population are also asking for diversity of partnerships, especially bringing in Russia and an estrangement with traditional partners operating with non-traditional partners and private actors, including military companies like the Wagner Group in the case of Mali.”

In the context of uncertainties, she said there were some risks with the emerging role of the security partners and the diversification of non-traditional and non-state actors in the security of the West Africa region and for Ghana in particular.

Risk to Coastal West Africa

Dr Soulè said the worsening security situation across the Sahel had amplified already existing tensions.

She said there were some risks of spillover effects with increased violence and volatility for Coastal West Africa evidenced in the northern regions of Ghana and countries sharing borders with Sahelian countries.

Following attacks recently in Northern Togo perpetrated by groups, many of them linked to international terrorist networks, 750 people sought refuge in northern Benin.

The same, perhaps, was happening in northern Ghana and although there has not been any terrorist attack, there is an influx of Burkinabe asylum seekers in the country.

Ghana, Dr Soulè said had avoided waves of Islamist violence that had destabilised its neighbours in the Sahel and that there were some situations in northern Ghana, especially Bawku where escalating political conflicts near the border with Burkina Faso could be used as an opportunity by the groups to target the country.

She said there were some legal and humanitarian concerns because security partners (private military companies) like Wagner in Mali were growing their clout in the region and offering, very openly, the risk of having to deal with certain types of actors that could not be legally held accountable by the United Nations.

“There is also an increase in violation of human rights like murders perpetrated in some of the villages in Mali in the name of the fight against terrorism,” she noted.

Growing insecurity, threats

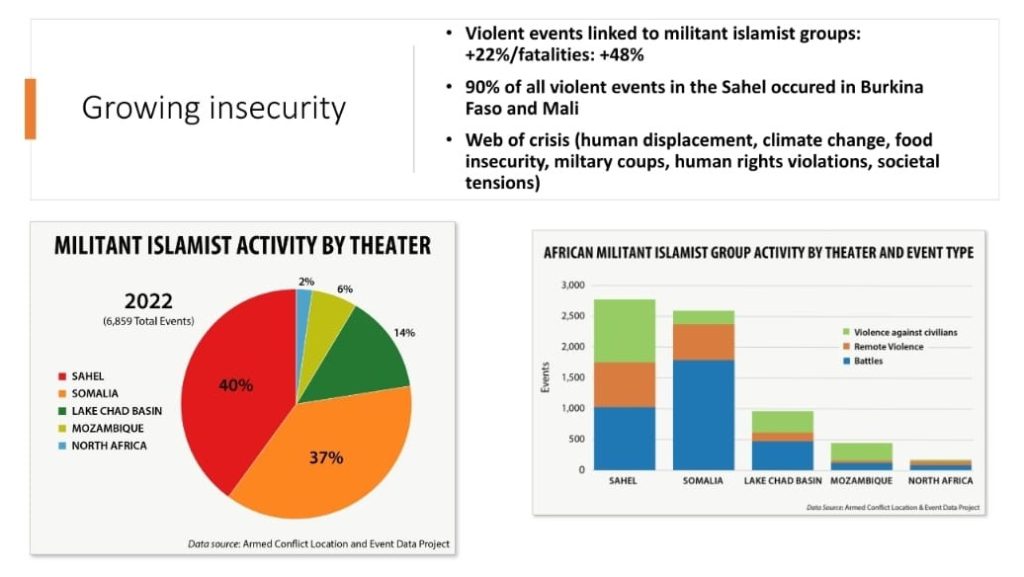

According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), violent events linked to Militant Islamist groups in Africa increased by 22 per cent and fatalities switched by 48 per cent.

Militant Islamist violence in the Sahel accounted for 77 per cent of the total violent events across Africa in 2022.

Out of that, 90 per cent of all violence occurred in the Sahel more specifically Burkina Faso and Mali which means that the Sahel alone accounted for 40 per cent of all violent activity by Militant and Islamist Groups in Africa more than any other in the world.

Dr Soulè, also a Visiting Scholar at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD), therefore, said the worrying statistics were embedded in a “web of crises” including human displacements, adding that as of December 2022, there were more than 2.6 million people displaced.

Also, she added that climate change and its accompanying shocks was high in a region where 80 per cent of people lived directly off the land with Sahel temperatures rising faster than the global average and shortening the rainy season.

She mentioned food security and the effects of COVID-19 as issues that had forced almost five million people in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger and four million people in the Lake Chad Basin into severe food security.

The Oxford Scholar explained that democratic backsliding, especially manifested by the different coups and extended failures of governments to meet their people’s needs had fuelled both the violence and surge of armed Coup d’état.

Other elements, including human rights violations, she noted, were increasing violence as between 2019 and early 2021, the United Nations and other organisations had documented more than 600 unlawful killings by state security forces and forced disappearances and other abuses as part of the heavily securitised response to terrorism.

She said societal tensions and ongoing violence had ripped apart the local fabric that once held local communities together with some very specific groups mostly scapegoated and stigmatised.

In that context, she said, Traditional Security Partnerships were being called into question, explaining that France’s Army had been the traditional partner of many Francophone countries even though it was expedition-oriented especially in Francophone West Africa.

Dr Folashade Soulè reiterated that the diversification of security partnership impacted on the peace and security in the Sahel, maintaining that the increased attacks in response to heavily securitised-focused strategies or approach of Sahelian armies had not curbed such attacks in Mali, but had heightened it with terrorist attacks even progressing.

Regional Cooperation

A cooperative and collaborative security mechanism anchored on information and intelligence sharing to sustain border security is key to reducing the influence of security partners in the Sahel.

To that effect, Dr Soulè speaking in an interview with the Ghana News Agency, said there had been an increased cooperation in the region particularly the role of ECOWAS and effective interventions like the Accra Initiative.

The Accra initiative, which has Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo, is in response to growing insecurity linked to violent extremism in the region and aims to prevent a spillover of terrorism from the Sahel.

That, Dr Soulè, said, was commendable and a positive development, which required the strengthening of such cooperations.

In conclusion, Dr Folashade Soulè, said as much as Security Partnership was an agreement between two governments, it was also an agreement with the people and that negotiating better security partnerships was necessary.

According to her, if the agreements and partnerships were not properly negotiated and communicated with the right synergy, there waa a risk of divergent interests and increasing defiance by public opinions.

Dr Chekwuemeka B. Eze, Executive Director, West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), said it was time for a critical reflection on the geopolitics on how the new influence was going to affect the region in the long run.

“How do we begin to define who a security partner is? If this type of partnership is furthering the whole idea of state centric security at the expense of human security and welfare, then we are in trouble. These are guys that are coming to sell military hardware with eyes on the natural resources in the region.”

That, he said, would not lead to the rebuilding of the economy of the Sahel region or translate in investment in women as key drivers of the economy at that level which would further lead to security not being defined by the regions.

GNA